Green space is important for wellbeing but in poorer areas visits to parks have dropped.

Official government guidance during lockdown advises us to “enjoy nature” and exercise outside once a day. When accessing green spaces, people should “stay local” while keeping “at least two metres apart from anyone outside your household”. These conditions are necessary, but their impacts will be unequal. If we don’t want the pandemic to exacerbate a mental health crisis, we need to address these inequalities. At NEF we’ve found that while the proportion of people visiting parks or public green spaces has almost halved, this reduction is much more pronounced in poorer local authorities than wealthier ones.

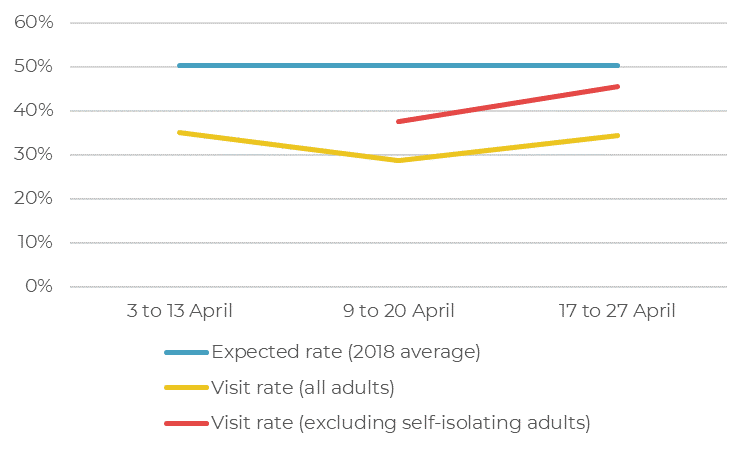

The government’s weekly data release covering 17 to 27 April shows that only 34.5% of the population reported visiting a park or public green space in the past seven days – a slight increase on the previous week’s data (see figure below). Our analysis of 2018 data suggests that, pre-pandemic, the average proportion of the population who would report visiting parks and green spaces in the past seven days would be closer to 50%. Given the glorious weather in April, this is likely an underestimate of the true proportion of the population who would have been out in parks and green spaces in normal times. Using this 50% baseline we can calculate that at least 8 million fewer adults were visiting parks and green spaces than would usually be expected. If we adjust for those who are self-isolating and unable to go out, we calculate that at least 5 million adults were deterred from going out to parks and green spaces due to the crisis.

Figure: Rates of green space use in April 2020 compared with the 2018 average. Source: NEF analysis of ‘Coronavirus and the social impacts on Great Britain’ (ONS) and data from Fields in Trust.

These statistics should be interpreted carefully as the numbers are crude and many drivers will be at play. At the headline level they indicate that the UK public are rightly being cautious during the lockdown. However, they might also be interpreted as a failure on the part of government to provide safe access to green space in a time of social distancing.

Further NEF analysis, conducted on a Google dataset showing the movements of the UK population against government income data shows very different trends between poorer and richer local authorities. Where data was available, the poorest 20 local authorities reported an average 28% reduction in the use of parks compared to the baseline period, meanwhile the wealthiest 20 local authorities reported no change in park use.

The reasons for these differences across income groups are complex, related to factors like sectors of work, working patterns, pre-existing health conditions and age. Key workers, for example, are more likely to live in poorer areas and may not have the time right now to enjoy green space. But these figures also relate to inequities in proximity to green space. Not all households have green spaces near to their homes. Houses located closer to green spaces are higher in price, suggesting that wealthier people have better access. And when properly provisioned, we know that access to good quality green space can be a ‘levelling’ factor, which reduces disparities in wellbeing across different groups.

Good access does not necessarily mean increased use, especially in a time of social distancing. Visits may not be a welcoming prospect as many parks are overcrowded. From the limited research available, we know that in deprived areas local green space is most stretched and prone to overcrowding. One study in Sheffield showed that population pressure on green space could be approximately 60% higher in the bottom income quintile compared to the top.

Latest guidance from the police clarifies that households may drive to reach the countryside, as long as “far more time is spent walking than driving”. But for many, this is of no help. Many households do not own a car and public transport is not currently an option. Those households are concentrated in the lowest income quintile, where almost half of households are without a car.

Wealthier households are also more likely to have larger gardens, and many poorer households have no garden at all. For some households, gardens will provide minimum exposure to green space, but the number of households across the UK without a garden has been on the increase. While well intentioned, advice from Public Health England that those without a garden grow a plant on their windowsill feels hollow.

There’s less research into how gender and race affect access to green space. One study in Bradford ascertained that areas with higher green space access typically had more white residents than areas with lower accessibility, which had more Asian and Asian-British residents. Natural England found that children from low-income and Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) households are less likely to frequently visit urban or rural wild places than white children or those from higher income households.

Extensive evidence shows that living in greener urban areas is associated with reduced mental stress and increased life satisfaction. Our analysis shows that in poorer areas, which already have limited access to green space, green space use has dropped the furthest. Data in the government’s latest release highlights that more than one in five (21.2%) adults in the UK population believe that the coronavirus crisis is making their mental health worse. We should be concerned about the acceleration of a mental health crisis. There are a number of factors that could trigger mental health problems and distress over the coming months: poor housing conditions, job insecurity, financial hardship and more. Accessing green space isn’t a substitute for addressing these problems alone but should be part of a wider package of support for individuals.

As the crisis continues to highlight and amplify pre-existing inequities, we must make sure that the barriers to accessing good quality green spaces are removed. Data crunching is urgently required to identify hotspots which lack safe access to public green space. In these areas government and local authorities must work together to deliver fair access. Private green spaces must immediately be opened to public use. Golf courses, the grounds of private schools and stately homes, and London’s garden squares in particular must be targeted. But while these steps will help some, it will only be a minority. With support from health experts, the government must also commit to measures which at least facilitate safe outdoor exercise and bring in sufficient mental health support.

Looking beyond the immediate health crisis, delivering wellbeing through improved access to green space must be addressed in any upcoming fiscal stimulus or investment package. For many years, town planning in the UK has sacrificed green space access at the altar of developer profits and we are now paying the price with our mental wellbeing. A significant programme of rewilding, shifts in agricultural practices, and restoration of nature is imperative in order to prevent climate and ecological breakdown and can also expand green space access. In order to build policy solutions for more inclusive access to green space, it is essential to understand the experiences of different groups of people and how race, gender and wealth intersect. Any recovery programme must be carefully oriented to ensure it redresses social inequities and provides better quality green space to more people.

The call to make better wellbeing the principle objective of our coronavirus recovery strategy is getting louder. To do so, we must look closer at our use and access of parks and green space.

Notes

The 50% baseline figure for how many adults were visiting parks pre-pandemic assumes that April 2020 was representative of the 2018 UK average in regard to the weather and seasonal conditions which affect people’s behaviours. In order to establish whether it is appropriate to compare use of parks and green space in April 2020 with the annual average for 2018 we considered a systematic academic literature review by Liu et al. 2017. Of the weather and seasonal factors which influence active travel and use of outdoor space the most important drivers are: temperature, rainfall, hours of sunshine, and day length. In all regards, April 2020 had above-average conditions, i.e. conditions more optimal for going outside, than the annual average. Temperatures were above average, rainfall was below average, sunshine was above average, and day length was (slightly) above the annual average. Indeed, April 2020 was provisionally the sunniest on record. As such, the annual average rate of green space/park use for 2018 of 50.3% is likely an underestimate of the rate which would normally be expected given conditions in April 2020.

The figure of 5 million adults deterred from visiting parks adjusts for all those who did not leave the house due to self-isolating in the past seven days, according to figure published in the ONS release “Coronavirus and the social impacts on Great Britain”.

The 28% reduction in the use of parks compared to the baseline period includes national parks, public beaches, marinas, dog parks, plazas and public gardens.

The baseline for the data provided by Google is January 3 to February 6 2020. Google’s decision to use this as a baseline (the mid-winter months) likely results in a lesser degree of change than if the data had been compared against data from April in a previous year.

Google did not provide data for four of the poorest, and one of the richest local authorities. The next most poor/rich authorities were used instead.

Study on the racial disparities of access to green space in Bradford is Ferguson et al. (2018). Contrasting distributions of urban green infrastructure across social and ethno-racial groups. Landscape and Urban Planning (175), pages 136 – 148.

Evidence on the wellbeing effects of living in a greener area from White et al (2013). Would You Be Happier Living in a Greener Urban Area? A Fixed-Effects Analysis of Panel Data. Psychological Science 24(6), pages 920 – 928.

Image: Flickr, public domain